| |

Two:

Every time I refer to my mum and dad as Pete and Hillary, you go pink

and tighten your lips.

Three: When you first talked to Pete and---all right, I'll let you off---when

you first talked to Mum and Dad, you let them go on and on about private

education and private health and how terrible it was and how evil the

government is and you never said a word. About your dad being a Tory MP,

I mean. You talked beautifully about the weather and incomprehensibly

about cricket. But you never let on.

That's what the row today was about, in fact. Your dad was on Weekend

World at lunchtime, you prolly saw him. (I love you, by the way. God,

I love you so much.)

"Where do they find them?" barked Pete, stabbing a finger at the television.

"Where do they find them?"

"Find who?" I said coldly, gearing up for a fight.

"Whom," said Hillary.

"These tweed-jacketed throwbacks," said Pete. "Look at the old fart. What

right has he got to talk about the miners? He wouldn't recognize a lump

of coal if it fell into his bowl of Brown Windsor soup."

"You remember the boy I brought home last week?" I said, with what I'm

pretty sure any observer would call icy calm.

"Job security, he says!" Pete yelled at the screen. "When have you ever

had to worry about job security, Mr. Eton, Oxford, and the Guards?" Then

he turned to me. "Hm? What, boy? When?"

He always does that when you ask him a question---says something else

first, completely off the subject, and then answers your question with

one (or more) of his own. Drives me mad. (So do you, darling Neddy. But

mad with deepest love.) If you were to say to my father, "Pete, what year

was the battle of Hastings?" he'd say, "They're cutting back on unemployment

benefit. In real terms it's gone down by five percent in just two years.

Five percent. Bastards. Hastings? Why do you want to know? Why Hastings?

Hastings was nothing but a clash between warlords and robber barons. The

only battle worth knowing about is the battle between . . ." and he'd

be off. He knows it drives me mad. I think it prolly drives Hillary mad

too. Anyway, I persevered.

"The boy I brought home," I said. "His name was Ned. You remember him

perfectly well. It was his half term. He came into the Hard Rock two weeks

ago."

"The Sloane Ranger in the cricket jumper, what about him?"

"He is not a Sloane Ranger!"

"Looked like one to me. Didn't he look like a Sloane Ranger to you, Hills?"

"He was certainly very polite," Hillary said.

"Exactly." Pete returned to the bloody TV, where there was a shot of your

dad trying to address a group of Yorkshire miners, which I have to admit

was quite funny. "Look at that! First time the old fascist has ever been

north of Watford in his life, I guarantee you. Except when he's passing

through on his way to Scotland to murder grouse. Unbelievable. Unbelievable."

"Never mind Watford, when did you last go north of Hampstead?" I said.

Well, shouted. Which was fair I think, because he was driving me mad and

he can be such a hypocrite sometimes.

Hillary went all don't-you-talk-to-your-father-like-that-ish and then

got back to her article. She's doing a new column now, for Spare Rib,

and gets ratty very easily.

"You seem to have forgotten that I took my doctorate at Sheffield University,"

Pete said, as if that qualified him for the Northerner of the Decade Award.

"Never mind that," I went on. "The point is Ned just happens to be that

man's son." And I pointed at the screen with a very exultant finger. Unfortunately

the man on camera just at that moment was the presenter.

Pete turned to me with a look of awe. "That boy is Brian Walden's son?"

he said hoarsely. "You're going out with Brian Walden's son?"

It seems that Brian Walden, the presenter, used to be a Labour MP. For

one moment Pete had this picture of me stepping out with socialist royalty.

I could see his brain rapidly trying to calculate the chances of his worming

his way into Brian Walden's confidence (father-in-law to father-in-law),

wangling a seat in the next election and progressing triumphantly from

the dull grind of the Inner London Education Authority to the thrill and

glamour of the House of Commons and national fame. Peter Fendeman, maverick

firebrand and hero of the workers, I watched the whole fantasy pass through

his greedy eyes. Disgusting.

"Not him!" I said. "Him!" Your father had appeared back on-screen again,

now striding towards the door of Number Ten with papers tucked under his

arm.

I love you, Ned. I love you more than the tides love the moon. More than

Mickey loves Minnie and Pooh loves honey. I love your big dark eyes and

your sweet round bum. I love your mess of hair and your very red lips.

They are very red in fact, I bet you didn't know that. Very few people

have lips that really are red in the way that poets write about red. Yours

are the reddest red, a redder red than ever I read of, and I want them

all over me right now-but oh, no matter how red your lips, how round your

bum, how big your eyes, it's you that I love. When I saw you standing

there at Table Sixteen, smiling at me, it was as if you were entirely

without a body at all. I had come out of the kitchen in a foul mood and

there shining in front of me I saw this soul. This Ned. This you. A naked

soul smiling at me like the sun and I knew I would die if I didn't spend

the rest of my life with it.

But still, how I wished this afternoon that your father were a union leader,

a teacher in a comprehensive school, the editor of the Morning Star, Brian

Walden himself-anything but Charles Maddstone, war hero, retired Brigadier

of the Guards, ex-colonial administrator. Most of all, how I wish he was

anything but a cabinet minister in a Conservative government.

That's not right though, is it? You wouldn't be you then, would you?

When Pete and Hillary both got it, they stared from me to the screen and

back again. Hillary even looked at the chair you sat in the day you came

round. Glared at the thing as if she wanted it disinfected and burned.

"Oh, Portia!" she said in what they used to call "tragic accents."

Pete, of course, after going as red as Lenin, swallowed his rage and his

baffled pride and began to Talk to me. Solemnly. He Understood my adolescent

revolt against everything I had been brought up to cherish and believe.

No, more than that, he Respected it. "Do you know, in a kind of way, I'm

proud of you, Porsh? Proud of that fighting spirit. You're pushing against

authority, and isn't that what I've always taught you to do?"

"What?" I screeched. (I have to be honest. There's no other word. It was

definitely a screech.)

He spread his hands and raised his shoulders with an infernal smugness

that will haunt me till the day I die. "Okay. You've dated the upper-class

twit of the year and that's got your dad's attention. You've got Pete

listening. Let's talk, yeah?"

I mean . . .

I arose calmly, left the room, and went upstairs for a think.

Well that's what I should have done but I didn't.

In fact I absolutely yelled at him. "Fuck you, Pete! I hate you! You're

pathetic! And you know what else? You're a snob. You're a hideous, contemptible

snob!" Then I stamped out of the room, slammed the door, and ran upstairs

for a cry. The President of the Immortals, in Aeschylean phrase, had finished

his sport with Portia.

Poo. And more poo.

Anyway, at least they know now. Have you told your parents? I suppose

they'll hit the roof as well. Their beloved son ensnared by the daughter

of Jewish left-wing intellectuals. If you can call a part-time history

lecturer at North East London Polytechnic an intellectual, which in my

book you can't.

It wouldn't be love without opposition, would it? I mean, if Juliet's

dad had fallen on Romeo's neck and said, "I'm not losing a daughter, I'm

gaining a son," and Romeo's mum had beamed, "Welcome to the Montague family,

Juliet my precious," it would be a pretty short play.

Anyway, a couple of hours after this "distressing scene," Pete knocked

on my door with a cup of tea. Precision, Portia, precision---he knocked

on my door with his knuckles, but you know what I mean. I thought he was

going to give me grief, but in fact---well no in fact he did give me grief.

That is exactly and literally what he gave me. He had just had a phone

call from America. Apparently Pete's brother, my uncle Leo, had a heart

attack in New York last night and was dead by the time an ambulance arrived.

Too grim. Uncle Leo's wife Rose died of ovarian cancer in January and

now he's gone, too. He was forty-eight. Forty-eight and dead from a heart

attack. So my poor cousin Gordon is coming over to England to stay with

us. He was the one who had to call the ambulance and everything. Imagine

seeing your own father die in front of you. He's the only child, too.

He must be in a terrible state, poor thing. I hope he'll like it with

us. I think he was brought up quite orthodox, so what he'll make of family

life here, I can't imagine. Our idea of kosher is a bacon bagel. I've

never met him. I've always pictured him as having a black beard, which

is insane of course, since he's about our age. Seventeen going on eighteen,

that kind of thing.

The result of the day is that peace has broken out in the Fendeman home

and next week I shall have a brother to talk to. I'll be able to talk

about you.

Which, O Neddy mine, is more than you ever do. "Won a match. Played pretty

well I think. Revising hard. Thinking about you a great deal." I quote

the interesting bits.

I know you're busy with exams, but then so am I. Don't worry. Any letter

that comes from you gives me a fever. I look at the writing and imagine

your hand moving over the paper, which is enough to make me wriggle like

a lovesick eel. I picture your hair flopping down as you write, which

is enough to make me writhe and froth like a . . . like a . . . er, I'll

come back to you on that one. I think of your legs under the table and

a million trillion cells sparkle and fizz inside me. The way you cross

a "t" makes me breathless. I hold the back of the envelope to my lips

and think of you licking it and my head swims. I'm a dotty dippy dozy

dreadful delirious romantic and I love you to heaven.

But I wish wish wish you weren't going back to your school next term.

Leave and be free like the rest of us. You don't have to go to Oxford,

do you? I wouldn't go to any university that made me stay on through the

winter term after I'd already done all my A levels and all my friends

had left, just to sit some special entrance paper. How pompous can you

get? Why can't they behave like a normal university? Come with me to Bristol.

We'll have a much better time.

I shan't bully you about it, though. You must do whatever you want to

do.

I love you, I love you, I love you.

I've just had a thought. Suppose your History of Art teacher hadn't taken

your class on a trip to the Royal Academy that Saturday? Suppose he had

taken you to the Tate or the National Gallery instead? You wouldn't have

been in Piccadilly and you wouldn't have gone to the Hard Rock Cafe for

lunch and I wouldn't be the luckiest, happiest, most dementedly in-love

girl in the world.

The world is very . . . um . . . (consults the Thomas Hardy textbook that

she's supposed to be studying) . . . the world is very contingent.

So there.

I'm kissing the air around me.

Love and love and love and love and love

Your Portia X

Only one X, because a quintillion wouldn't be anything like

enough.

7th June 1980

My darling Portia

Thank you for a wonderful letter. After your (completely justified) criticism

of my terrible style of letter-writing, this is going to be completely

tricky. It just seems to gush out of you like a geezer (spelling?) and

I'm not too hot at that kind of thing. Also your handwriting is completely

perfect (like everything else about you of course) and mine is completely

illegible. I thought of responding to your little extra (which was fantastic,

by the way) by spraying this envelope with eau de cologne or aftershave,

but I haven't got any. I don't suppose the linseed oil I use for my cricket

bat would entice you? Thought not.

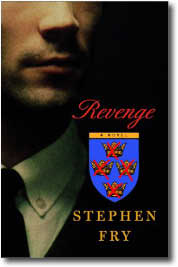

Excerpted

from Revenge by Stephen Fry Copyright 2002 by Stephen Fry. Excerpted

by permission of Random House, a division of Random House, Inc. All rights

reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without

permission in writing from the publisher.

|

|

(back

to top)

Synopsis

A distinct

departure from his popular comic novels, this haunting, provocative tale

of wrongful imprisonment and violent retribution is Stephen Fry’s

first thriller. A brilliant recasting of the classic story The Count of

Monte Cristo, Revenge crackles with the wit and intelligence readers have

come to expect from this hugely talented author, actor, and comedian,

yet it reveals an intriguingly deep, much darker side of his imagination.

Ned Maddstone

is a happy, charismatic Oxford-bound seventeen-year-old whose rosy future

is virtually preordained. Handsome, confident, and talented, newly in

love with bright, beautiful Portia, his father an influential MP, Ned

enjoys an existence of boundless opportunity. But privilege makes him

an easy target for envy, and in the course of one day Ned’s charmed

life is changed forever. A promise made to a dying teacher combined with

a prank devised by a jealous classmate mutates bewilderingly into a case

of mistaken arrest and incarceration. Drugged and disoriented, Ned finds

himself a political prisoner in a nightmarish, harrowing exile, far from

home and lost to those he loves. Years pass before an apparently mad,

obviously brilliant fellow inmate reawakens the younger man’s intellect

and resurrects his will to live. The chilling consequences of Ned’s

recovery are felt worldwide.

While Revenge

breaks new ground with its taut plotting, exhilarating pace, and underlying

air of menace, its sophistication and irreverent humor are vintage Fry—a

gloriously rich mix that only he could deliver. His first novel in four

years is a dramatic, powerful tour de force that is sure to enlarge the

American audience for this singularly talented author’s work.

(back

to top)

Author

Stephen

Fry was

born in Hampstead, London in 1957. He is an actor, aviator, comedian,

cricket fan, novelist, poet, playwright, screenwriter and rector of Dundee

University. As an actor he has been featured in numerous films, including

Gosford

Park, A Civil Action, and Wilde,

in which he played the title role, and in such popular English TV series

as Jeeves and Wooster, Black Adder, and A Bit of Fry

and Laurie. He lives in London. Stephen

Fry was

born in Hampstead, London in 1957. He is an actor, aviator, comedian,

cricket fan, novelist, poet, playwright, screenwriter and rector of Dundee

University. As an actor he has been featured in numerous films, including

Gosford

Park, A Civil Action, and Wilde,

in which he played the title role, and in such popular English TV series

as Jeeves and Wooster, Black Adder, and A Bit of Fry

and Laurie. He lives in London.

|

Stephen

Fry was

born in Hampstead, London in 1957. He is an actor, aviator, comedian,

cricket fan, novelist, poet, playwright, screenwriter and rector of Dundee

University. As an actor he has been featured in numerous films, including

Gosford

Park, A Civil Action, and Wilde,

in which he played the title role, and in such popular English TV series

as Jeeves and Wooster, Black Adder, and A Bit of Fry

and Laurie. He lives in London.

Stephen

Fry was

born in Hampstead, London in 1957. He is an actor, aviator, comedian,

cricket fan, novelist, poet, playwright, screenwriter and rector of Dundee

University. As an actor he has been featured in numerous films, including

Gosford

Park, A Civil Action, and Wilde,

in which he played the title role, and in such popular English TV series

as Jeeves and Wooster, Black Adder, and A Bit of Fry

and Laurie. He lives in London.