|

The widow to whom he handed the token, a small woman whose eyes barely came up to the counter, brought her fingers together and bobbed her head. "Thank you, sahib, thank you, you'll see to it that I get my money today, won't you?" she muttered and some of his ill temper was assuaged. Babu was embarrassed to be standing in this prison of paper-crammed cubicles with his father, feeling trapped by the pensioners as they flapped around awkwardly, filling up the passageway with their birdlike bodies. Experiencing at first hand the humiliation of being old and at the mercy of the state, he felt a sudden empathy for his father, who suffered this every month. But, feeling the minutes wasting away, he wished he could be somewhere else. The narrow corridor was lit by electric lights even in the morning, while beyond the teller windows all he could see was an endless sequence of rooms, disturbingly similar, like a series of receding reflections in parallel mirrors. Outside, Babu knew, the streets were full of people, the town and its inhabitants alike released from the long hibernation of winter by the touch of spring. The pension office was located in a hollow between the Additional Secretariat and the Governor's House, along the small road that ran from Police Bazaar toward the State Central Library situated inconspicuously at the heart of the government section that bordered the main commercial zone of the town. On his walk to the pension office, Dr. Dam, therefore, was forced to revisit those imposing structures of power he had been so much a part of until the year before. The Additional Secretariat had been built some years after the Principal Secretariat, when the hill region broke away from the state of Assam to form an independent political entity in 1972. The new hill state found itself with an old capital town -- after all, the town had been the capital of Assam from the time of the British -- and although it welcomed possession of the old building, it felt the necessity of erecting fresh monuments to the vastly different political aspirations of the hill people. The time of its self-assertion had left its mark on the architectural style of the Additional Secretariat and you could read the seventies in it as surely as if the decade was etched onto its facade. It was a rather large administrative complex for a town of this size, a poseur of a big city office block whose white concrete and tall glass panes had been beaten into a template of dull stains by the monsoon weather. Towering over the street, the view from its windows reduced pedestrians passing below to mere specks. When Dr. Dam and Babu had passed the building earlier in the morning, their anonymity was not challenged by the slightest flicker of recognition from within. They had walked on and waited for the turbaned military policeman directing traffic to wave them through to the pension building, where they joined the flow of hopeful pensioners: bent old men with memories of office, widows who put thumb imprints on official documents, and disabled men of an uncertain age who lounged around with a faint aura of alcohol about them. Work, that is the disbursement of money, did not begin until after lunch, although the pensioners had to hand in their Pension Payment Orders (PPOs) at counter three by eleven o'clock in the morning. The counter closed after the clerk had accepted the PPOs and given out numbered, round brass tokens. What happened between eleven and two when the numbers were finally called out was uncertain, but in some ways it was the most important procedure of the day. It usually ended with some of the supplicants being summarily rejected, while the lucky ones were given slips of paper that they exchanged for checks at counter five. A slightly different system was followed for those who received cash -- these were people whose monthly pensions amounted to less than three hundred rupees -- but barring the few who claimed to have a close relative among the clerks, the entire sequence was fraught with that strange mixture of tension and boredom that only a practiced bureaucracy is capable of producing.

|

||

|

(back

to top)

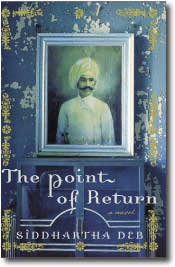

Synopsis Set in the remote northeastern hills of India, the story revolves around the father-son relationship of a willful curious boy, Babu, and Doctor Dam, an enigmatic product of British colonial rule and Nehruvian nationalism. Told in reverse chronological order, the novel examines an India where the ideals that brought freedom from colonial rule are beginning to crack under the pressure of new rebellions and conflicts. For Dr. Dam and Babu this has meant living as strangers in the same home, puzzled and resentful, tied only by blood. As the father grows weary and old and the son tries to understand him, clashes between ethnic groups in their small town show them to be strangers to their country as well. Before long Babu finds himself embarking on a great journey, an odyssey through the memories of his father, his family, and his nation. The Point of Return poignantly explores the precarious balance of familial relationships built around secrets and the intrusions of political conflicts outside the control of individuals. From start to finish it is a powerful, moving, and unforgettable story. (back to top)Author

|

©1998-2012 MostlyFiction.com |