| |

'Murdered

her?' she said then. 'Nancy? Why, I had her here an hour ago. She was

only beat a bit about the face. She has her hair curled different now,

you wouldn't know he ever laid his hand upon her.'

I said, 'Won't he beat her again though?'

She told me then that Nancy had come to her senses at last, and left Bill

Sykes entirely; that she had met a nice chap from Wapping, who had set

her up in a little shop selling sugar mice and tobacco.

She lifted my hair from about my neck and smoothed it across the pillow.

My hair, as I have said, was very fair then -- though it grew plain brown,

as I got older -- and Mrs Sucksby used to wash it with vinegar and comb

it till it sparked. Now she smoothed it flat, then lifted a tress of it

and touched it to her lips. She said, 'That Flora tries to take you on

the prig again, you tell me -- will you?'

I said I would. 'Good girl,' she said. Then she went. She took her candle

with her, but the door she left half-open, and the cloth at the window

was of lace and let the street-lamps show. It was never quite dark there,

and never quite still. On the floor above were a couple of rooms where

girls and boys would now and then come to stay: they laughed and thumped

about, dropped coins, and sometimes danced. Beyond the wall lay Mr Ibbs's

sister, who was kept to her bed: she often woke with the horrors on her,

shrieking. And all about the house-laid top-to-toe in cradles, like sprats

in boxes of salt-were Mrs Sucksby's infants. They might start up whimpering

or weeping any hour of the night, any little thing might set them off.

Then Mrs Sucksby would go among them, dosing them from a bottle of gin,

with a little silver spoon you could hear chink against the glass.

On this night though, I think the rooms upstairs must have been empty,

and Mr Ibbs's sister stayed quiet; and perhaps because of the quiet, the

babies kept asleep. Being used to the noise, I lay awake. I lay and thought

again of cruel Bill Sykes; and of Nancy, dead at his feet. From some house

nearby there sounded a man's voice, cursing. Then a church bell struck

the hour-the chimes came queerly across the windy streets. I wondered

if Flora's slapped cheek still hurt her. I wondered how near to the Borough

was Clerkenwell; and how quick the way would seem, to a man with a stick.

I had a warm imagination, even then. When there came footsteps in Lant

Street, that stopped outside the window; and when the footsteps were followed

by the whining of a dog, the scratching of the dog's claws, the careful

turning of the handle of our shop door, I started up off my pillow and

might have screamed -- except, that before I could the dog gave a bark,

and the bark had a catch to it, that I thought I knew: it was not the

pink-eyed monster from the theatre, but our own dog, Jack. He could fight

like a brick. Then there came a whistle. Bill Sykes never whistled so

sweet. The lips were Mr Ibbs's. He had been out for a hot meat pudding

for his and Mrs Sucksby's supper.

'All right?' I heard him say. 'Smell the gravy on this...'

Then his voice became a murmur, and I fell back. I should say I was five

or six years old. I remember it clear as anything, though. I remember

lying, and hearing the sound of knives and forks and china, Mrs Sucksby's

sighs, the creaking of her chair, the beat of her slipper on the floor.

And I remember seeing-what I had never seen before -- how the world was

made up: that it had bad Bill Sykeses in it, and good Mr Ibbses; and Nancys,

that might go either way. I thought how glad I was that I was already

on the side that Nancy got to at last -- I mean, the good side, with sugar

mice in.

It was only many years later, when I saw Oliver Twist a second time, that

I understood that Nancy of course got murdered after all. By then, Flora

was quite the fingersmith: the Surrey was nothing to her, she was working

the West End theatres and halls -- she could go through the crowds like

salts. She never took me with her again, though. She was like everyone,

too scared of Mrs Sucksby.

She was caught at last, poor thing, with her hands on a lady's bracelet;

and was sent for transportation as a thief.

*

We were all more or less thieves, at Lant Street. But we were that kind

of thief that rather eased the dodgy deed along, than did it. If I had

stared to see Flora put her hand to a tear in her skirt and bring out

a purse and perfume, I was never so surprised again: for it was a very

dull day with us, when no-one came to Mr Ibbs's shop with a bag or a packet

in the lining of his coat, in his hat, in his sleeve or stocking.

'All right, Mr Ibbs?' he'd say.

'All right, my son,' Mr Ibbs would answer. He talked rather through his

nose, like that. 'What you know?'

'Not much.'

'Got something for me?'

The man would wink. 'Got something, Mr Ibbs, very hot and uncommon...'

They always said that, or something like it. Mr Ibbs would nod, then pull

the blind upon the shop-door and turn the key -- for he was a cautious

man, and never saw poke near a window. At the back of his counter was

a green baize curtain, and behind that was a passage, leading straight

to our kitchen. If the thief was one he knew he would bring him to the

table. 'Come on, my son,' he would say. 'I don't do this for everyone.

But you are such an old hand that -- well, you might be family.' And he

would have the man lay out his stuff between the cups and crusts and tea-spoons.

Mrs Sucksby might be there, feeding pap to a baby. The thief would see

her and take off his hat.

'All right, Mrs Sucksby?'

'All right, my dear.'

'All right, Sue? Ain't you growed!'

I thought them better than magicians. For out from their coats and sleeves

would come pocket-books, silk handkerchiefs and watches; or else jewellery,

silver plate, brass candlesticks, petticoats -- whole suits of clothes,

sometimes. 'This is quality stuff, this is,' they would say, as they set

it all out; and Mr Ibbs would rub his hands and look expectant. But then

he would study their poke, and his face would fall. He was a very mild-looking

man, very honest-seeming-very pale in the cheek, with neat lips and whiskers.

His face would fall, it would just about break your heart.

'Rag,' he might say, shaking his head, fingering a piece of paper money.

'Very hard to push along.' Or, 'Candlesticks. I had a dozen top-quality

candlesticks come just last week, from a crib at Whitehall. Couldn't do

nothing with them. Couldn't give them away.'

He would stand, making a show of reckoning up a price, but looking like

he hardly dare name it to the man for fear of insulting him. Then he'd

make his offer, and the thief would look disgusted.

'Mr Ibbs,' he would say, 'that won't pay me for the trouble of walking

from London Bridge. Be fair, now.'

But by then Mr Ibbs would have gone to his box and be counting out shillings

on the table: one, two, three- He might pause, with the fourth in his

hand. The thief would see the shine of the silver -- Mr Ibbs always kept

his coins rubbed very bright, for just that reason -- and it was like

hares to a greyhound.

'Couldn't you make it five, Mr Ibbs?'

Mr Ibbs would lift his honest face, and shrug.

'I should like to, my son. I should like nothing better. And if you was

to bring me something out of the way, I would make my money answer. This,

however' -- with a wave of his hand above the pile of silks or notes or

gleaming brass -- 'this is so much gingerbread. I should be robbing myself.

I should be stealing the food from the mouths of Mrs Sucksby's babies.'

And he would hand the thief his shillings, and the thief would pocket

them and button his jacket, and cough or wipe his nose.

And then Mr Ibbs would seem to have a change of heart. He would step to

his box again and, 'You eaten anything this morning, my son?' he would

say. The thief would always answer, 'Not a crust.' Then Mr Ibbs would

give him sixpence, and tell him to be sure and spend it on a breakfast

and not on a horse; and the thief would say something like,

'You're a jewel, Mr Ibbs, a regular jewel.'

Mr Ibbs might make ten or twelve shillings' profit with a man like that:

all through seeming to be honest, and fair. For of course, what he had

said about the rag or the candlesticks would be so much puff: he knew

brass from onions, all right. When the thief had gone, he'd catch my eye

and wink. He'd rub his hands again and grow quite lively.

'Now, Sue,' he'd say, 'what would you say to taking a cloth to these,

and bringing up the shine? And then you might -- if you've a moment, dear,

if Mrs Sucksby don't need you -- you might have a little go at the fancy

work upon these wipers. Only a very little, gentle sort of go, with your

little scissors and perhaps a pin: for this is lawn -- do you see, my

dear? -- and will tear, if you tug too hard...'

I believe I learned my alphabet, like that: not by putting letters down,

but by taking them out. I know I learned the look of my own name, from

handkerchiefs that came, marked Susan. As for regular reading, we never

troubled with it. Mrs Sucksby could do it, if she had to; Mr Ibbs could

read, and even write; but, for the rest of us, it was an idea -- well,

I should say, like speaking Hebrew or throwing somersaults: you could

see the use of it, for Jews and tumblers; but while it was their lay,

why make it yours?

So I thought then, anyway. I learned to cipher, though. I learned it,

from handling coins. Good coins we kept, of course. Bad ones come up too

bright, and must be slummed, with blacking and grease, before you pass

them on. I learned that, too. Silks and linens there are ways of washing

and pressing, to make them seem new. Gems I would shine, with ordinary

vinegar. Silver plate we ate our suppers off -- but only the once, because

of the crests and stampings; and when we had finished, Mr Ibbs would take

the cups and bowls and melt them into bars. He did the same with gold

and pewter. He never took chances: that's what made him so good. Everything

that came into our kitchen looking like one sort of thing, was made to

leave it again looking quite another. And though it had come in the front

way -- the shop way, the Lant Street way-- it left by another way, too.

It left by the back. There was no street there. What there was, was a

little covered passage and a small dark court. You might stand in that

and think yourself baffled; there was a path, however, if you knew how

to look. It took you to an alley, and that met a winding black lane, which

ran to the arches of the railway line; and from one of those arches --

I won't say quite which, though I could -- led another, darker, lane that

would take you, very quick and inconspicuous, to the river. We knew two

or three men who kept boats there. All along that crooked way, indeed,

lived pals of ours -- Mr Ibbs's nephews, say, that I called cousins. We

could send poke from our kitchen, through any of them, to all the parts

of London. We could pass anything, anything at all, at speeds which would

astonish you. We could pass ice, in August, before a quarter of the block

should have had a chance to turn to water. We could pass sunshine in summer

-- Mr Ibbs would find a buyer for it.

In short, there was not much that was brought to our house that was not

moved out of it again, rather sharpish. There was only one thing, in fact,

that had come and got stuck -- one thing that had somehow withstood the

tremendous pull of that passage of poke -- one thing that Mr Ibbs and

Mrs Sucksby seemed never to think to put a price to.

I mean of course, Me.

I had my mother to thank for that. Her story was a tragic one. She had

come to Lant Street on a certain night in 1844. She had come, 'very large,

dear girl, with you,' Mrs Sucksby said -- by which, until I learned better,

I took her to mean that my mother had brought me, perhaps tucked in a

pocket behind her skirt, or sewn into the lining of her coat. For I knew

she was a thief. -- 'What a thief!' Mrs Sucksby would say. 'So bold! And

handsome?'

'Was she, Mrs Sucksby? Was she fair?'

'Fairer than you; but sharp, like you, about the face; and thin as paper.

We put her upstairs. No-one knew she was here, save me and Mr Ibbs --

for she was wanted, she said, by the police of four divisions, and if

they had got her, she'd swing. What was her lay? She said it was only

prigging. I think it must have been worse. I know she was hard as a nut,

for she had you and, I swear, she never murmured -- never called out once.

She only looked at you, and put a kiss on your little head; then she gave

me six pounds for the keeping of you -- all of it in sovereigns, and all

of 'em good. She said she had one last job to do, that would make her

fortune. She meant to come back for you, when her way was clear...'

So Mrs Sucksby told it; and every time, though her voice would start off

steady it would end up trembling, and her eyes would fill with tears.

For she had waited for my mother, and my mother had not come. What came,

instead, was awful news. The job that was meant to make her fortune, had

gone badly. A man had been killed trying to save his plate. It was my

mother's knife that killed him. Her own pal peached on her. The police

caught up with her at last. She was a month in prison. Then they hanged

her.

They hanged her, as they did murderesses then, on the roof of the Horsemonger

Lane Gaol. Mrs Sucksby stood and watched the drop, from the window of

the room that I was born in.

You got a marvellous view of it from there -- the best view in South London,

everybody said. People were prepared to pay very handsomely for a spot

at that window, on hanging days. And though some girls shrieked when the

trap went rattling down, I never did. I never once shuddered or winked.

'That's Susan Trinder,' someone might whisper then. 'Her mother was hanged

as a murderess. Ain't she brave?'

I liked to hear them say it. Who wouldn't? But the fact is -- and I don't

care who knows it, now -- the fact is, I was not brave at all. For to

be brave about a thing like that, you must first be sorry. And how could

I be sorry, for someone I never knew? I supposed it was a pity my mother

had ended up hanged; but, since she was hanged, I was glad it was for

something game, like murdering a miser over his plate, and not for something

very wicked, like throttling a child. I supposed it was a pity she had

made an orphan of me -- but then, some girls I knew had mothers who were

drunkards, or mothers who were mad: mothers they hated and could never

rub along with. I should rather a dead mother, over one like that!

I should rather Mrs Sucksby. She was better by chalks. She had been paid

to keep me a month; she kept me seventeen years. What's love, if that

ain't? She might have passed me on to the poorhouse. She might have left

me crying in a draughty crib. Instead she prized me so, she would not

let me on the prig for fear a policeman should have got me. She let me

sleep beside her, in her own bed. She shined my hair with vinegar. You

treat jewels like that.

And I was not a jewel; nor even a pearl. My hair, after all, turned out

quite ordinary. My face was a commonplace face. I could pick a plain lock,

I could cut a plain key; I could bounce a coin and say, from the ring,

if the coin were good or bad. -- But anyone can do those things, who is

taught them. All about me other infants came, and stayed a little, then

were claimed by their mothers, or found new mothers, or perished; and

of course, no-one claimed me, I did not perish, instead I grew up, until

at last I was old enough to go among the cradles with the bottle of gin

and the silver spoon, myself. Mr Ibbs I would seem sometimes to catch

gazing at me with a certain light in his eye -- as if, I thought, he was

seeing me suddenly for the piece of poke I was, and wondering how I had

come to stay so long, and who he could pass me on to. But when people

talked -- as they now and then did -- about blood, and its being thicker

than water, Mrs Sucksby looked dark.

'Come here, dear girl,' she'd say. 'Let me look at you.' And she'd put

her hands upon my head and stroke my cheeks with her thumbs, brooding

over my face. 'I see her in you,' she'd say. 'She is looking at me, as

she looked at me that night. She is thinking, that she'll come back and

make your fortune. How could she know? Poor girl, she'll never come back!

Your fortune's still to be made. Your fortune, Sue, and ours along with

it...'

So she said, many times. Whenever she grumbled or sighed -- whenever she

rose from a cradle, rubbing her sore back -- her eyes would find me out,

and her look would clear, she'd grow contented.

But here is Sue, she might as well have said. Things is hard

for us, now. But here is Sue. She'll fix 'em...

I let her think it; but thought I knew better. I'd heard once that she'd

had a child of her own, many years before, that had been born dead. I

thought it was her face she supposed she saw, when she gazed so hard at

mine. The idea made me shiver, rather; for it was queer to think of being

loved, not just for my own sake, but for someone's I never knew...

I thought I knew all about love, in those days. I thought I knew all about

everything. If you had asked me how I supposed I should go on, I dare

say I would have said that I should like to farm infants. I might like

to be married, to a thief or a fencing-man. There was a boy, when I was

fifteen, that stole a clasp for me, and said he should like to kiss me.

There was another a little later, who used to stand at our back door and

whistle 'The Locksmith's Daughter', expressly to see me blush. Mrs Sucksby

chased them both away. She was as careful of me in that department, as

in all others.

'Who's she keeping you for, then?' the boys would say. 'Prince Eddie?'

I think the people who came to Lant Street thought me slow. -- Slow I

mean, as opposed to fast. Perhaps I was, by Borough standards. But it

seemed to me that I was sharp enough. You could not have grown up in such

a house, that had such businesses in it, without having a pretty good

idea of what was what -- of what could go into what; and what could come

out.

Do you follow?

*

You are waiting for me to start my story. Perhaps I was waiting, then.

But my story had already started -- I was only like you, and didn't know

it.

*

This is when I thought it really began.

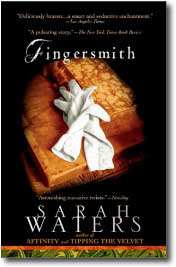

From Fingersmith

by Sarah Waters, Copyright (c) February 2002, Riverhead books, a division

of Penguin Putnam, Inc., used by permission.

From Fingersmith,

by Sarah Waters. � January 31, 2002 , Riverhead Books used by permission.

|