| |

"That's

all right." She smiled, feeling sexy as she put her watch back on in front

of the guard. "I love getting frisked," she said. "It's better than having

a husband."

Past security, she continued down a hallway and into an empty reception

area. With the swearing-in taking place across the river, most of the

Pentagon was closed down for the afternoon. Kay had known George Bush

for years, and had high hopes for his presidency. The media take on the

new president as some sort of bumbling idiot was a joke. As anyone who

knew the real story would tell you, Bush was the balls. Even back

in '73, it was Bush who'd urged President Nixon to ignore the Democrats,

to insist upon his beloved rationale, national security, even if it meant

endorsing a few indiscretions. This might not have been very good advice,

but it certainly wasn't cowardly. It always made Kay smile, the American

public's willingness to manufacture its own misinformation.

On the third floor, she caught up to Mitchell Frenkle, deputy director

of the DCA. He walked carefully, trying not to spill his coffee on his

way past the elevators. "Hi, Kay. Recognize the joint?"

"Sure, it never changes."

The man groaned. "Well, we like to play around with our acronyms every

now and again, but what the hell."

The door to Frenkle's office opened automatically as they reached the

end of the corridor. Swissshhh . . . space age! Kay looked over

her shoulder, nervous around these hi-tech contraptions. The door closed

behind them.

"Look who's here," Frenkle said. His outer office was spacious, with three

secretaries' desks and a leather sofa, some magazines on the coffee table.

A middle-aged man in a light suit half-rose from the sofa and shook Kay's

hand.

"NSF, I'm Barney Crain," he said. "It's nice to meet you, Mrs. Tree."

Christ, she thought. First the branch, then the name-these people in Washington

sure have some weird priorities.

Still holding Kay's hand, Crain asked, "When are you folks over at Georgetown

going to send us some decent interns?"

Kay took her hand back. "When we have some decent students, Mr. Crain."

It was returning to her now, the Washington josh. Almost a form of social

currency in these parts.

Frenkle broke in: "Crain is head statistician for the National Science

Foundation. He'll be working with us today." He led the way into the next

room and closed the door. On his desk, an answering machine fluttered

its red eye-six quick flashes and then a pause. He shook his head. "I

tell people to use the e-mail, they don't listen."

"Give it time." Crain tossed a pair of high-density floppies onto a round

conference table and settled into his chair. Hitting Play on the answering

machine, Frenkle listened to his messages, the usual Inauguration Day

blather.

"Hi, Muh-Mitch? Thuh-this is Dan here." Coughing, the voice deepened.

"That's Mister VeePee to you, pal, heh-heh. Just kiddin' there.

Luh- listen-"

"Shut the fuck up." Frenkle deleted the message, then joined the others

at the table. Crouching down, he inserted both disks into a hard drive

and hit the power button. The lights dimmed theatrically as a sixty-inch

monitor came down from the ceiling. On the screen, a blue image showed

an outline of the forty-eight contiguous states. White lines curved from

one point to another, like missiles launched and exploded halfway across

the country.

Blinking at the bright screen, Crain resumed his original thought. "Telephones

are so bloody old-fashioned, it's pathetic. Even the utility companies

have wised up. I still remember AT&T, back in '64, '65, AT&T telling

Paul Baran that packet switching was a doomed concept. Now they're all

lining up. You'd think this was the only thing we do."

Kay tried not to listen as the two men traded inside jokes about the eggheads

at AT&T. She hated computer talk. She'd been around it ever since

coming to Washington in 1969, and to this day she still favored the lunchtime

solitude of her office to the chatter of these swashbuckling men with

their hi-tech delusions. Who among them could muster up the same passion

for a Strauss opera, those last liquid moments of Der Rosenkavalier,

say, with the voices seeking chromaticism and yet still reaching with

a backwards longing for the court and parlor? Macheath always preferred

Verdi to Strauss, but he and Kay never argued about such trifles. So the

man had a thing for "La donna � mobile," so what? At least he had a wide

range of interests. Botany, yes, of course, and glassmaking, but also

Scottish literature, typography, Bauhaus art and architecture, combat

theory, semantics, even cross-country skiing. He cared about things,

you see. For all their talk of the coming information revolution, men

like Frenkle and Crain were ignorant of the world beyond the network.

These men craved information, but only for its statistical value. Information

was something to be channeled, transmitted, systematically converted,

broken down into packets and later reassembled as text and color. The

last thing anyone wanted to do was read it.

"Kay, we're looking at an overview of the system as it stands today. I'm

sure you've seen something like it before."

She pulled her glasses out of her purse, then peered up at the screen.

"I don't know," she said. "I haven't been paying much attention lately."

"Kay's been too busy teaching cryptology to graduate students," Frenkle

said, making it sound like an indulgence, a housewife's distraction. Kay's

been taking a pottery class on Wednesdays.

"God, how dull," Crain muttered. "What's to teach?"

"Not much, I guess," Kay said. This was something her youngest daughter,

Lydia, had never learned. Around men, sometimes it's best just to let

things go. Leaning back in her seat, she added, "The most promising

students, I pass on. I send them across the river to Frenkle."

"Where they are never heard from again,' he laughed with insane abandon."

Pleased with his joke, Frenkle cut the banter short. "Anyway. Here nor

there."

"Agreed. So, Kay, to bring you up to date . . ." Crain tapped the mouse

button, causing the image on the screen to fade behind a grid. "Ignore

all that. I'm sure you're familiar with the old ARPANET."

Frenkle glared across the table. "Jumping the gun a bit, aren't you Crain?"

"Old, new, whatever, we need to start somewhere." A new picture hovered

across the screen, depicting the original four IMPs set up by Bolt Beranek

and Newman in the late sixties. Seeing this again, Kay remembered the

time, her own life back then. Things were different when her husband was

still alive. Macheath's world was a world of slow communications, where

one had to choose each word carefully, for every mistake meant endless

backtracks, cross-outs, crumpled pages in the trash can. Had he not died

in 1968, would he too have shelved such habits in favor of newer, speedier

modes of communication? Had technology itself brought about this blanding

of shared thought?

"As you can see," continued Crain, dragging his mouse to erase the map.

"That system has since been replaced by a larger, more complicated array

of nodes."

Annoyed, Frenkle set down his coffee. "You write it off so easily," he

said. "Those IMPs supported our activities for nearly two decades."

"Relax, Mitch. Credit due. But we all knew years ago that the network

eventually would grow beyond the capacities of any single agency. If it

didn't, we would've failed."

Frenkle folded his arms. "I just want Kay to understand the topography

as it stands."

The two men stared at each other, then smiled. It really was silly, in

a way. This whole thing.

"Okay, Mitch. Good point." As Crain spoke, different views of the network

passed across the screen-very professional, just like a movie. "It is

now January 1989. The IMPs of the past are largely worthless, since high-speed

routers-manufactured by IBM and maintained by the Gloria Corporation-provide

us with a more efficient means of controlling traffic. This new development,

quite naturally, will diminish the role the Defense Communications Agency

plays in determining network priorities."

"Getting out of the computer business, Mitchell?" Kay smiled.

Frenkle paused to finish the last of his coffee. "We'll always be around,

Kay," he said.

Crain continued his presentation. "The demographic makeup of groups using

these networks will change dramatically over the next few years. With

the rise of personal computers, the Net will soon host dozens-possibly

hundreds-of sites maintained by unknown individuals. Security issues will

become more and more of a factor. The need to keep a clear perspective

on where information is originating from, how it moves along the network,

and where it winds up is of critical importance."

"I sense a bottom line around here somewhere."

"Oh, she's good."

"Of course she is, Barney," said Frenkle. "It's Kay's job to see the words

behind the words."

"Well, since you asked, the problem is this." On the screen, the map gave

way to a drawing of an RS/6000, T-3 compatible bit processor. Flow arrows

demonstrated a progression through an in point, into a computer core,

and then out along a variety of links. The diagram did not indicate the

size of the contraption; it could have been as tiny as Frenkle's teacup

or as large as the Pentagon itself.

"What is it?" Kay asked.

"The Gloria 21169. Your key to a better future."

"It's a router," Frenkle snapped. Crain's sense of dramatics seemed to

be getting on his nerves.

"It's a very bad router. Or so we think. Let me bore you with some theory

for a moment." More symbols, more diagrams. The picture on the screen

clarified nothing, even though Crain's tone of voice suggested that it

did. "The network has always functioned as a hierarchy of layers. This

is not likely to change. It only makes sense that as long as there is

a network, there will be a distribution of roles. This is the nature of

systems."

"Take a tip from Uncle Sam." Frenkle rubbed his nose, feinting at each

nostril with a bent finger. January allergies rustled in the throats of

both men.

Crain continued: "Routers are specialized computers designed to conduct

the flow of traffic. Certain routers handle business within autonomous

networks. Other routers are configured to serve as an interface between

two distinct networks."

"The Gloria machine," Kay said, unsure of herself. She did not mind Crain's

pedantic tone; while she'd worked with network prototypes for many years,

she'd always utilized preexisting software and thus knew very little about

computers on the bare-bones level. As a cryptographer, it was her job

to scramble the thoughts of others, not to devise ones of her own. "So

we've got a computer that doesn't know what it's doing."

Here, Crain seemed genuinely puzzled. "Maybe . . . but I don't think so.

Let me explain." He set his pen down on the table. "Do you remember Bob

Kahn?" Kay did; she'd seen him at MIT in the mid-sixties, and in Washington

a few years later when she was hired to create a cipher for the TCP/IP

project. "In the early days of the ARPANET, Kahn outlined four basic principles

central to network communications. The first three, I don't remember."

He looked at Frenkle, who shrugged-search me. "The fourth rule

was simple. There can be no global consolidation of power in a system

of this size." He sighed. Through the thick, tinted windows of the Pentagon,

the noise of the inaugural parade sounded dull and ominous, like the boom

of an underground explosion. "It seems the Gloria router may not have

gotten the message."

"I don't understand." Kay rubbed her eyes, missing the clarity of a well-lit

room. "Weren't the Gloria routers manufactured according to the government's

own specifications?"

"They were, but so what?" Crain grabbed a sheet of paper and sketched

a diagram-positives and negatives and decimal expressions of relative

proportions. In the dark, Kay could read none of it. "Look. The way the

protocol's designed, a host computer sends a message. The router receives

information from the host describing where the message should wind up.

Based on that information, the router makes a decision. It can send the

message on to its destination; it can relay the message back to the host;

or it can redirect the message to another router. The important thing

is this: In order for the network to operate effectively, these decisions

must be made on the basis of the overall system. Each router has its own

role to play. These roles were determined when the network was set in

place."

"Sounds reasonable."

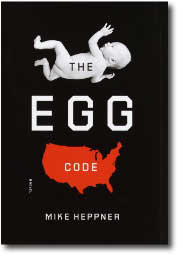

Excerpted from The Egg Code by Mike HeppnerCopyright

2002 by Mike Heppner. Excerpted by permission of Knopf, a division of

Random House, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be

reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

|

|

(back

to top)

Synopsis

With astonishing

scope, flair and originality, Mike Heppner’s debut explores our secret

lives and most desperate impulses even as they are penetrated by a global

web of mysterious provenance and dubious promise.

Few who live

in Big Dipper Township have even heard about anything called the Egg Code;

they’re busy enough as it is. At one end of this tiny Midwestern

community, a motivational speaker starts choking on his own words, while

at another, an impressionable dancer struggles to realize her recurrent

dreams of flying. An estranged wife becomes a counterfeit folklorist,

while an aging typographer is besieged by regret. And—in one household—a

“living arrangements” salesman is harried to the verge of losing

his livelihood, while his wife stage-mothers their talentless son and

eventually decides to take destiny into her own hands.

Also nearby,

however, is a lone hacker bent on destroying the demon among them all:

a router, the Gloria 21169, that, along with thousands of others, trafficks

in information from all the world over to comprise the Internet. But the

Gloria, or the corporation that controls it, has taken command of the

entire network, at a tremendous cost to this young man’s family and

to the consternation of parties on both sides of the technological revolution.

The crisscrossing

of these many lives reveals how much (if at all) these quantum shifts

in our society have affected our hopes, behavior and prospects. As much

Our Town as 2001, and as funny as it is suspenseful, The Egg Code

is both a hugely entertaining novel and the announcement of a spectacular

career.

(back

to top)

Author

Mike Heppner grew up in Grosse Pointe, Michigan, received an M.F.A. from Columbia University,

and now lives in Providence, Rhode Island.

|