|

As Brismand 1 neared the harbor I let my eyes travel across the water toward the esplanade. As a child I had liked it here; I'd often played on the beach, hiding under the fat bellies of the old beach huts while my father conducted whatever business he had at the harbor. I recognized the faded Choky parasols on the terrasse of the little caf� where my sister used to sit; the hot dog stand; the gift shop. It was perhaps busier than I remembered; a straggling row of fishermen with pots of crabs and lobsters lined the quay, selling their catch. I could hear music from the esplanade; below it, children played on a beach that, even at high tide, seemed smoother and more generous than I remembered. Things were looking good for La Houssini�re. I let my eyes roam along the Rue des Immortelles, the main street, which runs parallel to the seafront. I could see three people sitting there side by side in what had once been my favorite spot: the seawall below the esplanade overlooking the bay. I remembered sitting there as a child, watching the distant gray jawbone of the mainland, wondering what was there. I narrowed my eyes to see more clearly; even from halfway across the bay I could see that two of the figures were nuns. I recognized them now as the ferry drew close -- Soeur Extase and Soeur Th�r�se, Carmelite volunteers from the nursing home at Les Immortelles, were already old before I was born. I felt oddly reassured that they were still there. Both nuns were eating ice creams, their habits hitched up to their knees, bare feet dangling over the parapet. The man sitting beside them, face obscured by a wide-brimmed hat, could have been anyone. The Brismand 1 drew alongside the jetty. A gangplank was raised into place, and I waited for the tourists to disembark. The jetty was as crowded as the boat; vendors stood by selling drinks and pastries; a taxi driver advertised his trade; children with trolleys vied for the attention of the tourists. Even for August, it was busy. "Carry your bags, mademoiselle?" A round-faced boy of about fourteen, wearing a faded red T-shirt, tugged at my sleeve. "Carry your bags to the hotel?" "I can manage, thanks." I showed him my tiny case. The boy gave me a puzzled glance, as if trying to place my features. Then he shrugged and moved on to richer pickings. The esplanade was crowded. Tourists leaving; tourists arriving; Houssins in between. I shook my head at an elderly man attempting to sell me a knot work key ring; it was Jojo-le-Go�land, who used to take us for boat rides in summer, and although he'd never been a friend -- he was an Houssin, after all -- I felt a pang that he hadn't recognized me. "Are you staying here? Are you a tourist?" It was the round-faced boy again, now joined by a friend, a dark-eyed youth in a leather jacket who was smoking a cigarette with more bravado than pleasure. Both boys were carrying suitcases. "I'm not a tourist. I was born in Les Salants." "Les Salants?" "Yes. My father's Jean Prasteau. He's a boatbuilder. Or was, anyway." "GrosJean Prasteau!" Both boys looked at me with open curiosity. They might have said more, but just then three other teenagers joined us. The biggest addressed the round-faced boy with an air of authority. "What are you Salannais doing here again, heh?" he demanded. "The seafront belongs to the Houssins, you know that. You're not allowed to take luggage to Les Immortelles!" "Who..." The foregoing is excerpted from Coastliners by Joanne Harris. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced without written permission from HarperCollins Publishers, 10 East 53rd Street, New York, NY 10022 |

|

|

(back

to top)

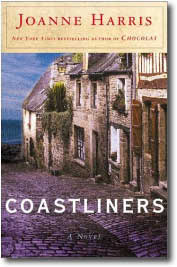

Synopsis Joanne Harris writes fiction that engages every one of the senses: reviewers called Chocolat "delectable" and Five Quarters of the Orange "sweet and powerful." In her new novel, she takes readers to a tiny French island where you can almost taste the salt on your lips. The island, called Le Devin, is shaped somewhat like a sleeping woman. At her head is the village of Les Salants, while the more prosperous village of La Houssinière lies at her feet. You could walk between the towns in an hour, but they could not feel further apart, for between them lie years of animosity. The townspeople of Les Salants say that if you kiss the feet of their patron saint and spit three times, something you've lost will come back to you. And so Madeleine, who grew up on the island, returns after an absence of ten years spent in Paris. She is haunted by this place, and has never been able to feel at home anywhere else. But when she arrives, she will find that her father -- who once built fishing boats that fueled the town's livelihood -- has become even more silent than ever, withdrawing almost completely into an interior world. And his decline seems reflected in the town itself, for when the only beach in Les Salants washed away, all tourism drifted back to La Houssinière. Madeleine herself has been adrift for a long time, yet almost against her will she soon finds herself united with the village's other lost souls is a struggle for survival and salvation. (back to top)Author

|

©1998-2012 MostlyFiction.com |

Joanne

Harris

was born in the North of England and as a girl lived in her grandparents'

candy shop in France. She is the great-granddaughter of a woman known

locally as a witch and a healer. Half-French, half-English, she taught

French at a school in Northern England. Her novel Chocolat was

nominated for the Whitbread Award, one of Britain's most prestigious literary

prizes.

Joanne

Harris

was born in the North of England and as a girl lived in her grandparents'

candy shop in France. She is the great-granddaughter of a woman known

locally as a witch and a healer. Half-French, half-English, she taught

French at a school in Northern England. Her novel Chocolat was

nominated for the Whitbread Award, one of Britain's most prestigious literary

prizes.