|

But catboats are well evolved for sailing over our particular shoals, and they turn out to be extraordinarily adaptable to contemporary life on the waters of the East Coast cities. Like a whale's body, the shape of a boat's hull and the arrangement of its rigging are evolutionary solutions to complex problems of life in particular marine surroundings. "The one essential factor in the design of boats proven by history," wrote maritime historian Howard Chappel, "is that they must fit the conditions where they are used and for what they are used. . . . No one sits down and tries to figure out how to build a boat that is all round ‘better.' He tries to figure out, instead, how to fit an existing boat so that she will do better the work for which she is required. This was certainly the case with the commercial catboat." It may no longer be well adapted for sport or commercial fishing, but the catboat was still ideal for family voyages. Tradition was small enough for one sailor to handle and relatively easy on a strained household budget. Her four-cylinder gas engine burned about fifty dollars worth of gasoline a season, from April to late October or November. Her eleven-foot width sat flat on the water; her great beam made her extremely accommodating. You couldn't stand in the cabin below, and every boating season began with at least one sharp knock on the head, but there was plenty of room below for a huge double berth, a small galley, a portable marine head, a long bookshelf, and assorted storage nooks. On deck there was room for ten people to go on a day's outing without feeling crowded. When they were young, our children slept under the stars on Tradition's broad deckhouse. Wandering along the beach outside the city one day, I spotted the rotting hulk of an open-decked sloop, draped it over the back of a rented truck, and hauled it back to a local lagoon. A village carpenter made the major repairs. I finished the boat and rigged it for sailing. On its maiden voyage, two African friends from my village took the chance of being the first to go out with me. A crowd of curious villagers lined the beach. (Their preferred watercraft was a sleek dugout canoe with a good fifteen-horse Johnson outboard.) We sailed off smartly, and I took a few tacks through the wind. Heading back to shore to pick up Susan for her turn, I forgot to raise the dagger board. The boat hit the bottom and rolled all three of us into about three feet of lagoon water. The entire village erupted in howls. Susan was in stitches. She hardly understood how little about sailing I actually knew. But always game, she came out with me and we sailed through some splendid tidal estuaries in the Ebrie Lagoon, behind the great ocean beaches. Seventeen years later, when we were settled in Long Beach on another estuary, I managed to get us out on the water again. Before I

bought Tradition, Susan teased me by saying, "If you've got to buy

another boat, just make sure it doesn't end up in the backyard like the

last one." The last one, a battered rowing skiff, had rotted in our

yard, proof I was probably not suited to taking proper care of a boat.

Still I pored over boat ads in the penny-savers. I had sailed a strong

open-decked catboat as a boy on family vacations in Maine with two old

salts who gave me lessons. Now and then one of the modern fiberglass catboats

would appear in the used boat ads, but they were always far too expensive

for us Tradition was lying in pieces in the back of her seller's cottage when we first set eyes on her. My son, Noah, and I had driven at the crack of dawn to Southold, on the north fork of Long Island, the day after we spotted the ad for her: "1910 Crosby Catboat, hull fiberglassed, engine, $2,500." The owner had assured me over the phone that the boat had been restored and that she was well worth taking a look at. It was 1979, and my father lay dying in Mt. Sinai hospital in Manhattan. I needed a lift. But as Noah and I surveyed Tradition's forlorn condition, settled into the lawn of a Southold backyard, under a ragged canvas cover, it was hard to know what to think. Her lines, her sturdiness, her ample deck and cockpit space, her wooden spars, and all the rest were evident. She was traditional, all right, but modified over the years and now facing an uncertain future, perhaps only as another backyard compost pile. My heart was beating wildly with the sudden panic of a man about to act like a boy by making an impulse purchase. I could hear all the voices of experience and reason telling me to get another opinion, shop around, try for a better price. Noah and I took a walk down Southold's Main Street and thought it over. Tradition's owner guaranteed that the engine had worked the last time the boat was in the water but did not say when that actually was. The prop turned easily, suggesting that the engine was not beyond hope, but the wiring looked abysmal. The modern Dacron sail was in good shape, however, and with its great size, that was important; a new one would cost almost the price of the boat itself. I could feel myself letting go. The beauty of the lines, the sheer breadth of her, the turn of her bilge, and the overhung transom had me. We took deep breaths. I paid the $2,500 asking price minus a token $100, to prove back home that we drove a hard bargain, and then made arrangements to have Tradition shipped to a working boatyard near our home on Reynolds Channel. When he saw our purchase, Howard Sacken, who in those days ran Sacken's Boatyard with his son Mark, was not pleased. He was downright grumpy. "This is a piece of shit," he muttered. "Look at that paint flaking off the hull, and those barnacles. You're going to have to take all that down bare before you can even begin to think about trying to fix the place on the keel around the prop where the fiberglass has failed." But Noah and I were determined: nothing would prevent us from getting Tradition in shape and sailing again. The work cleared the mind and reminded me that I was privileged not to have such work as a daily obligation. I stole hours in the early mornings and evenings during the week and put in some full days on the weekends. We sanded and scraped until we thought our arms would fall off. We showed Howard Sacken and the other salts that we were game. We pestered to have the wiring and other mechanical work done. We read and reread the advice in the marvelous journal of the Catboat Association. But as the weeks dragged by we worried that the craft might never measure up to our dreams. I took on additional research projects and wrote even more reports to pay the yard bills. We withstood the gentle teasing of Susan and Noah's sisters Eve and Johanna, and at times we coaxed them into chipping and painting with us. Howard Sacken could be tired, distracted and loath to explain how the work should proceed. But on good days, when he was not exhausted from the killing pace of labor in a family boatyard, or when he was not too exasperated by customers who ran their new boats into pilings or burned out their engines needlessly, he advised us on the nautical arts and crafts. When we finally launched the boat, it was the end of the 1980 sailing season, but we were so excited to have her in the water that we continued taking her out for short ventures until Thanksgiving. We sailed her up and down Reynolds Channel in some heavy fall wind to test her strength. We soon learned what a wonderful boat she was, but we also learned a good deal about her idiosyncrasies and faults. Tradition was slow. In a stiff breeze she could keep up with any sailboat her size and some even larger, but in lighter air she tended to flounder in the propeller wash of the powerboats that ripped through the channel. In a strong breeze she scooted along, even pointed well into the wind, but when the wind kicked up above twelve knots her immense sail required shortening, or reefing, immediately. Reefing a huge catboat sail can be a challenge. Her graceful boom reaching out beyond the stern was a fearsome opponent, capable of rewarding the careless sailor with a good crack on the head. Yet I was happy: I was after the benefits of slowing down and taking a longer look at things, and while Tradition got us to our destination under most conditions of seas and wind, she would not be hurried and we had to respect her limits. There is a picture I treasure in The Catboat Book, a collection of articles about the history and care of these boats. The photo features Wilton Crosby's work crew at the turn of the nineteenth century, a decade before they built Tradition. The seven workers, including Wilton Crosby of the famous Osterville boatbuilding family, pose in full sunlight before the open boathouse. They stand impassive, each holding some tools of the trade and looking as if he'd been caught on his way to a more serious task, all but Wilton Crosby wearing a worker's apron. Wilton Crosby

is older than the others. He stares away from the camera, perhaps at one

of his creations bobbing with the tide in Osterville Harbor. Surely those

men could not have imagined building anything but a capable, honest boat.

But wooden boats, no matter how proud their craftsmen were of their skills,

cannot last forever, nor did the Crosby brothers presume that they would.

Still, these versatile small boats often became such cherished members

of their families that they were coddled and nursed into a finicky old

age. Tradition, built in 1910, ranked as the fifteenth oldest of the original

wooden catboats still afloat, most of them built by the Crosbys. Despite her pedigree, Tradition was impure. Only her beautiful lines, her shape in and out of the water, and the pleasing configuration of her spars and rigging were original; she was really more of an idea than the physical embodiment of her Yankee history. Her hull and decks bore a thick fiberglass hide, covering the original wooden beams and planks, rotted and sistered here and there. The fiberglass coating was laid on years before by people who knew what they were doing. She must have been close to firewood when the work was done, because her centerboard was replaced with a three-and-a-half-foot steel keel that bolted through the hull and was a permanent addition to her underwater profile. On the South Shore of Long Island a fixed keel is an almost fatal flaw for a wide, shallow boat like Tradition, a flaw that counteracts the best qualities of such craft. With a retractable centerboard the catboat draws less than two or three feet of water, which means she is ideal for shoal waters on the bays and estuaries of the East Coast, able to run up on a beach at low tide and be lifted off by the flood tide with no difficulty. When she bumps against the bottom, you simply retract her centerboard and float away. Tradition had lost that versatility. She could get stuck on the bottom in four feet of water, and if the tide was high when she ran aground, she and her crew spent much extra time on the bay. Her prosthesis also did nothing for her sailing qualities. With a strong breeze over her beam, she bent into the wind with her sail full and her rigging creaking reassuringly. With a following wind nudging her from a hind quarter and her boom payed out, the gusts twisted her around that keel a bit and she wanted to get her nose into the wind, which may not have been a convenient direction, especially in a narrow channel. This weather helm, as it is known, is a problem of the catboat breed, but Tradition's untraditional keel worsened the condition. Despite those faults she carried our family over the waves for seventeen years and who knows how many other families before ours? After we fixed her up and nursed her into decent condition, Tradition let us and our friends see our world from the sea. But only if we were not in a great hurry. Copyright � 2002 William KornlbumReprinted with permission. |

|

|

(back

to top)

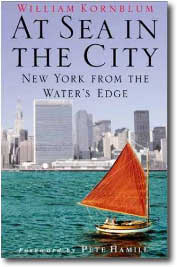

Synopsis New York is a city of few boundaries, a city of well-known streets and blocks that ramble on and on, into our literature, dreams, and nightmares. We know the city by the byways that split it, streets like Broadway and Madison and Flatbush and Delancey. From those streets, peering down the blocks and up at the top floors, the city seems immense and endless. And though the land itself may end at the water, the city does not. Long before Broadway was a muddy cart track, the water was the city's most distinguishing feature, the rivers the only byways of importance. Some people, like William Kornblum, still see the city as an urban archipelago, shaped by the water and the people who have sailed it for goods, money, pirate's loot, and freedom. For them, the City will always be an island. William Kornblum--New York City native, longtime sailor, urban sociologist--has spent decades plying the waterways of the city in his ancient catboat, Tradition. In AT SEA IN THE CITY, he takes the reader along as he sails through his hometown, lovingly retelling the history of the city's waterfront and maritime culture and the stories of the men and women who made the water their own. In AT SEA IN THE CITY and in Kornblum's own humility, humor, and sense of wonder, one detects echoes of E. B. White, John McPhee, and Joseph Mitchell. Amazon

readers rating: Author

|

©1998-2012 MostlyFiction.com |

William

Kornblum

is a professor of sociology at the City University of New York. He is

a graduate of Cornell University and the University of Chicago and was

among the nation’s first Peace Corps volunteers. He is the author

of numerous scholarly books and articles on the people of New York. A

native New Yorker, he’s been sailing around the city his whole life.

William

Kornblum

is a professor of sociology at the City University of New York. He is

a graduate of Cornell University and the University of Chicago and was

among the nation’s first Peace Corps volunteers. He is the author

of numerous scholarly books and articles on the people of New York. A

native New Yorker, he’s been sailing around the city his whole life.